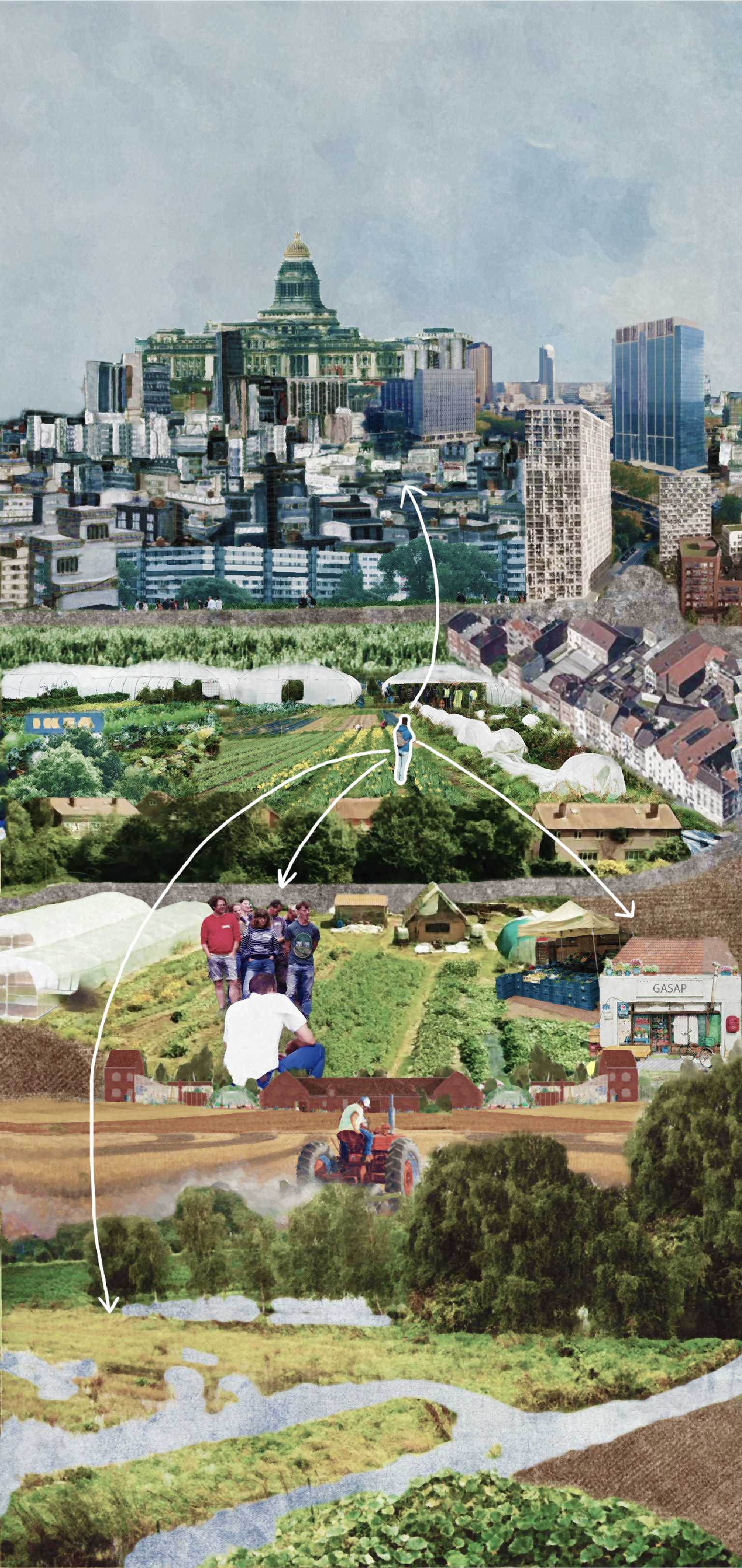

The dispersed urban context of Brussels and its fringe has yet to re-discover a key feature in light of the transition to an agroecological urbanism: proximity to open space. Several urban projects in Brussels are attempting to reactivate the agricultural land in the peri-urban and make it available for local production, starting with access to land but also developing the needed supporting infrastructure for a better access to market, knowledge and resources. How can this infrastructure benefit not only the new emerging Brussels maraîchers, but also the farmers in the Flemish and Walloon periphery?

The local food enabler sets up the needed connecting infrastructure to incubate local food systems, for both starting and transitioning farmers within Brussels and its surrounding regions.

Proximity

Historically, market gardeners in the fringes of Brussels, called Boerkozen or Maraîchers produced enough food to supply the whole of pre-industrial Brussels. The proximity to the city was key. The word 'Boerkoos' comes from the Old Dutch word ‘broek’, meaning 'swamp'. So a Boerkoos is a swamp dweller. The water-rich and fertile soils on the outskirts of the city were ideal for small-scale vegetable cultivation.

In the 20th century, the Boerkozen disappeared from the landscape. The post-war 'no more hunger' policy, the scaling-up and industrialisation of agriculture and the extension of suburbia pushed the Boerkozen's small-scale farming model away. Investments in infrastructure were geared towards the global model, of which Belgium's high road and port density are the result – often coming into conflict with the latent rural territory (see image). In general, it has disconnected Brussels even more from the agricultural community.

At the same time, Brussels is not comparable to other large Northern European Metropolises such as Paris or London. Unlike many other European countries, just about all of the Belgian territory has fallen prey to urbanisation. Brussels is part of a vast conurbation or Horizontal Metropolis: a more dense network of smaller cities covering large parts of northern France, Belgium, Luxemburg, western Germany and the Randstad of the Netherlands. In large, this now urbanised landscape matches the territory of the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt riverine delta.

As a result, open space is highly dispersed and fragmented. This fragmentation is problematic for several reasons. Just think of the numerous traffic jams, overpriced utilities or problems with flooding. On the other hand, it also has a unique quality: in fact, everything is close by! If you want to cycle from the centre of Paris to the nearest farm in a rural setting, it will take you at least an hour and a half. In Brussels it takes just twenty minutes, in any direction. We should cherish that proximity. It is an asset for the transition to healthy and local food production.

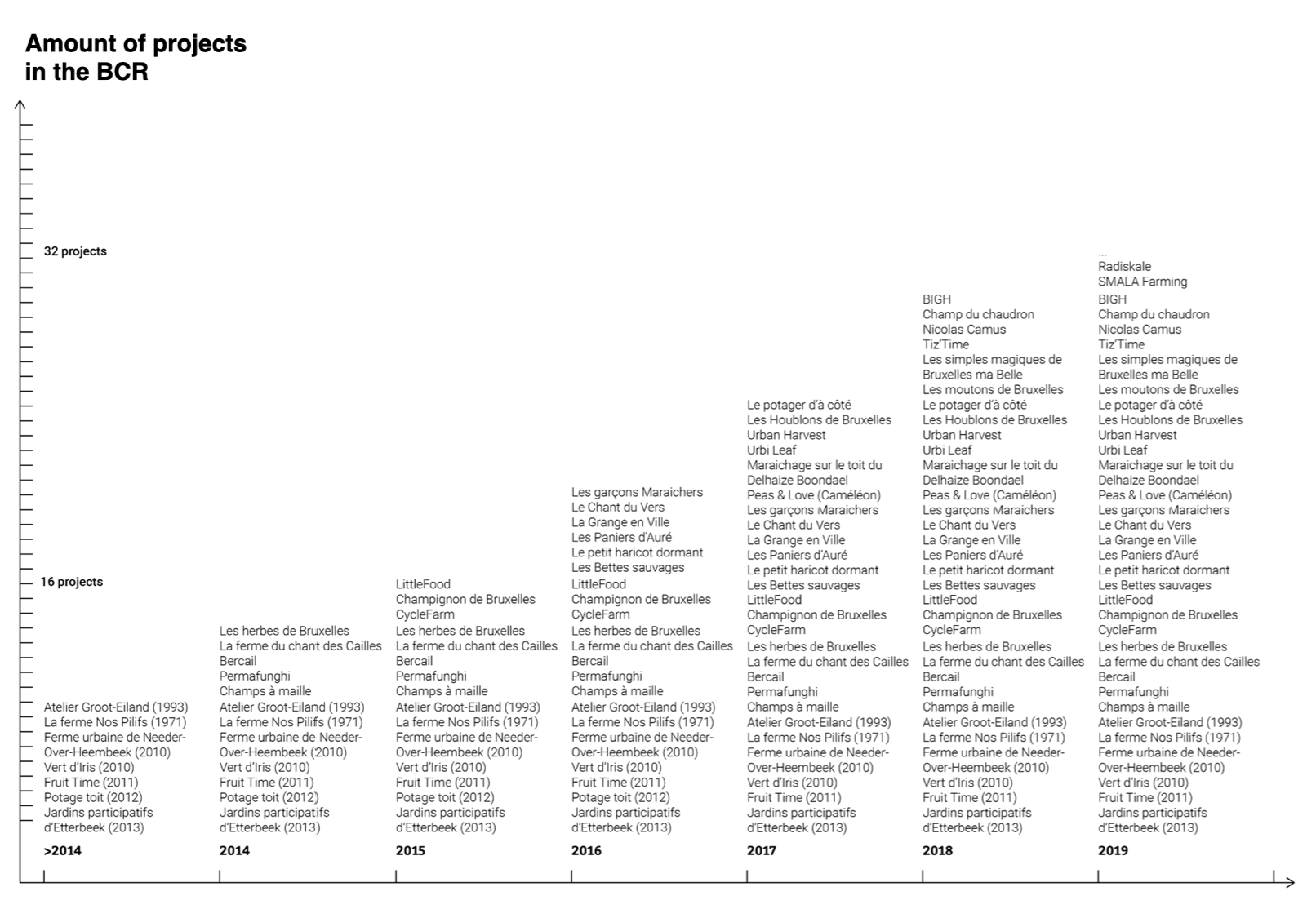

Today, we see that there are many efforts, based in Brussels, to revalue that proximity. As the graph shows, many new projects of urban agriculture have been set-up in recent years, both soil-based and non-soil based.

The infrastructure of the global industrial model is in conflict with the latent rural territory.

Timeline of the urban agriculture projects in Brussels

BoerenBruxselPaysans is a pilot project in the peri-urban fringe of Brussels seeking to offer new farmers the needed impulse to provide Brussels with local, healthy, qualitative and affordable food. Through the coalition of existing grassroots movements with government aid under the coordination of the Brussels regional authority and European funding, the project was able to set up a broad range of supportive infrastructure for starting farmers. The municipality of Anderlecht offers land as an espace-test or farmstart for farmers that want to test out their business model. The grassroots movement Début des Haricots offers practical training courses and links the test-farmers with their spin-off network GASAP—different consumer groups in the city of Brussels that are running a vegetable box-scheme. Maison Verte et Bleue runs a community kitchen and will help the local farmers to operate the future conserverie and packaging facility and Terre-en-vue, an access to land organisation, scouts more permanent and lasting land use agreements across the city for when farmers went through the testing period. The municipality of Anderlecht chose not to sell off residual agricultural infrastructure that marked the neighbourhood, but rather invest in the renovation and programming of these farm buildings to support growers and food initiatives in this part of the city. By focusing on infrastructure, BoerenBruxselPaysans creates literally the supporting environment that enables a constant inflow of new and transitioning farmers. It also creates a node in a wider landscape, holding the potential to offer their supporting infrastructure to many more farms in the area. Could we imagine the migration of the farm start to other locations, rather than moving the farmers that have invested in the soil and have in the meantime become networked within a local community?

Urban infrastructure for local food production

Among these, the most transformative project in terms of an agroecological urbanism is the social employment project BoerenBruxselPaysans, which has set up its first experimental and educational field in one of the last larger agricultural areas of Brussels, in Neerpede. The municipality of Anderlecht provides the land free of charge for three years. Grassroots organisation Début des Haricots and organic farmer Jean-Pierre provide technical guidance to would-be farmers. Financial expert Crédal advises on business models. And non-profit organisation Terre-en-Vue supports the search for new farmland for the farmers of tomorrow.

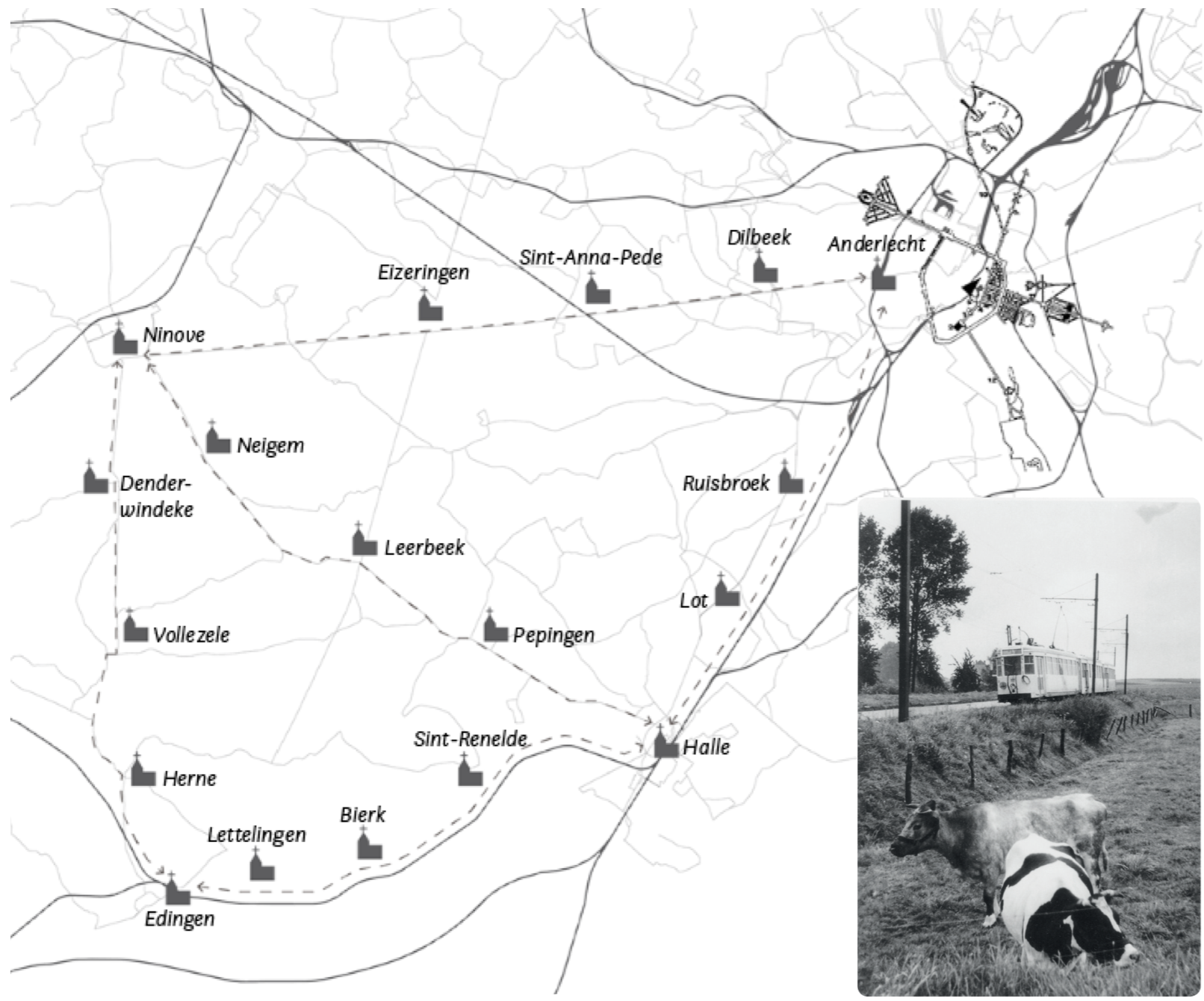

The BoerenBruxselPaysans project activated public land and provided training cultivation, processing and market support facilities as important assets to let new generations of Boerkozen start their career. But we can imagine other forms of infrastructure that enable local food production, also by looking back. There actually used to be a Farmer's tram (Boerentram), linking the centre of Brussels with the Pajottenlander farmers. What is the 21st century version of this type of infrastructure that allows to not only cater for the new and starting Brussels' farmers, but that can also help farmers in the periphery to transition and relocalize their activity? For example, there are French examples of mobile slaughter houses that have been shared within local farmer's networks.

A final example is how challenging it is to include conventional farmers in an agroecological transition. There is a great misunderstanding between the traditional large-scale and often family-based agricultural businesses and the new small-scale horticulturists. The local food enabler also has an important task in bridging these worlds by thinking like an agronomist. For example, there are two dairy farmers in Neerpede who mainly produce for the world market, but also offer raw milk in a farm shop. They do appeal to a local market, but because it concerns raw milk, that market is limited. But what if we as a society invest in the processing of that milk into a high-quality product (cheese, yoghurt,...) that generates a higher source of income and appeals to a wider local market? In this way, conventional farmers are also unburdened to organise the whole local chain themselves and they also have the financial capacity to farm more ecologically.

In other words, the local food enabler replaces a vast global farming system by picking up the missing links for the local food chain. The enabler then tries to build the needed infrastructure to bridge these missing links through public or public-private investments.The imaginaries around what this infrastructure could be, still need to be built. They will not come from policies, nor will they come from farmers if they do not organize themselves. The case of Rosario and the Programme of Urban Agriculture as well as the Spanish Network of Agroecological Municipalities are very inspiring for the Brussels territory, to not only enable farmers to collectively imagine the infrastructure to connect and set up local food chains but also to bridge the cultural gap and connect to the many farmers in the Flemish periphery of Brussels.

Visualization of the route of the Farmer’s tram from Brussels through the Pajottenland, together with photo The Farmer's tram in all its glory