No More Hunger

Steered by the post-war no more hunger credo, European Commissioner for Agriculture Sicco Mansholt strived for an increase in production and wanted to drastically reform the structure of European agriculture. He argued that farms were too small, farmers used too labour-intensive production methods and moreover they did not follow market developments closely. For Belgium, the country of smallholdings, this was a drastic change. The Plan Mansholt provoked enormous protests, with as its “highlight” the farmers’ demonstration of 23 March 1971 in Brussels [CAG]. But land consolidation projects were quickly being set up and from the 1950s onwards, started to group scattered, often smaller plots and tackled the construction or improvement of roads. The result was not only a scaling-up of farming land in general, but a very specific increase in grassland (pastures and meadows). Around 1880, less than 20% of Belgian agricultural land consisted of grassland. Shortly after the Second World War, that share fluctuated between 45% and 50%, particularly fueled by the increase of livestock aiming for the international market [CAG].

During the interbellum period, tractors were still a rarity in the Belgian fields. Pulling power then still comes mainly from horses. From 1950 onwards, however, mechanization had gained momentum: first there was the generalization of the tractor, later the introduction of the integrated machines that could perform several operations simultaneously [CAG]. The replacement of labour by machines and the growing need for modern and rational industrial buildings made agriculture increasingly capital intensive. Initially, it seemed worthwhile for the farmer to be responsible for the purchase of machines. But the complexity of the high-tech machines, plus the fact that many of them are only used for a short period every year, made the sector to a large extent evolving towards engaging specialized contract workers [CAG]. After the Second World War, scaling-up, mechanization, labour rejection and market impulses steered the farms gradually, but irreversibly, towards more dependence on external inputs and far-reaching specialization.

Sicco Mansholt driving the Twenty Two tractor during the flax harvest of 1939.

The Mixed Pajottenlander Farm

When mechanization rose in the post-war period, also the Pajottenland-Brussels region saw a scaling up of farming activities. Many smallholders quit, especially reducing the amount of Boerkozen, but giving way to the known typical Pajottenlander mixed family farm. These farms were generally larger than the Boerkozen plots, but were still very mixed, usually combining five to twenty dual-purpose cows with meadows, market-gardening and a small number of plots with wheat, barley, potatoes, beets and oats, often in a complex rotation system [Van den Abeele, 2018, p. 20]. What is interesting, however, is that, despite further scaling-up and specialization in the rest of Flanders, the Pajottenland was able to uphold this farming model for a strikingly longer period than anywhere else [Van den Abeele, 2018]. As we have seen in the previous chapter, the Pajottenland generally consisted of much more smallholding proprietors than anywhere else in the country. The leasing system in place gave relative freedom of cultivation to leaseholders, but landowners still had an influence on the future of the agricultural model used once a lease contract was ending. Small-scale proprietors had more autonomy. Greet Kerkhove and Lucas Van den Abeele elaborate on this in their theses and argue that the fact that the loamy Pajottenland region had the best soil of Belgium, made mixed farmers less dependent on resources, knowledge or machines (sandy soils in Antwerp needed a constant flow of fertilizer or manure, heavy clay soils in West-Flanders needed heavy machinery). Therefore, they could be selective in the help they sought, often holding a membership on multiple farmers unions at the same time (the Boerenbond, the General Farmers Syndicate ABS, but also Walloon ones). These unions were generally supporting the transition to larger scale farms but by dividing the power of these unions, agricultural unionism in the Pajottenland has never been ruled by one single organisation, making farmers much less dependent on and less sensitive to change than in other parts of the country [Kerkhove, 1994 and Van den Abeele, 2018, p. 21]. As a region bordering Wallonia, farmers active in the Pajottenland often felt more Walloon than Flemish, taking up much more of the progressive and socialist-inspired organisational forms, which was in stark contrast with conservative Flanders. Next to that, the most heavy specialisation first struck the more profitable and already larger scale arable farming rather than market-gardening, supporting infrastructure like the Boerentram was still in place and Brussels, as the biggest concentration of consumers in the country, remained for a long time a stable market [De Troch, 1981, p. 648].

The ‘kouter’ landscapes of Flanders close to villages were for a long time able to withstand the scaling up of international wheat trade

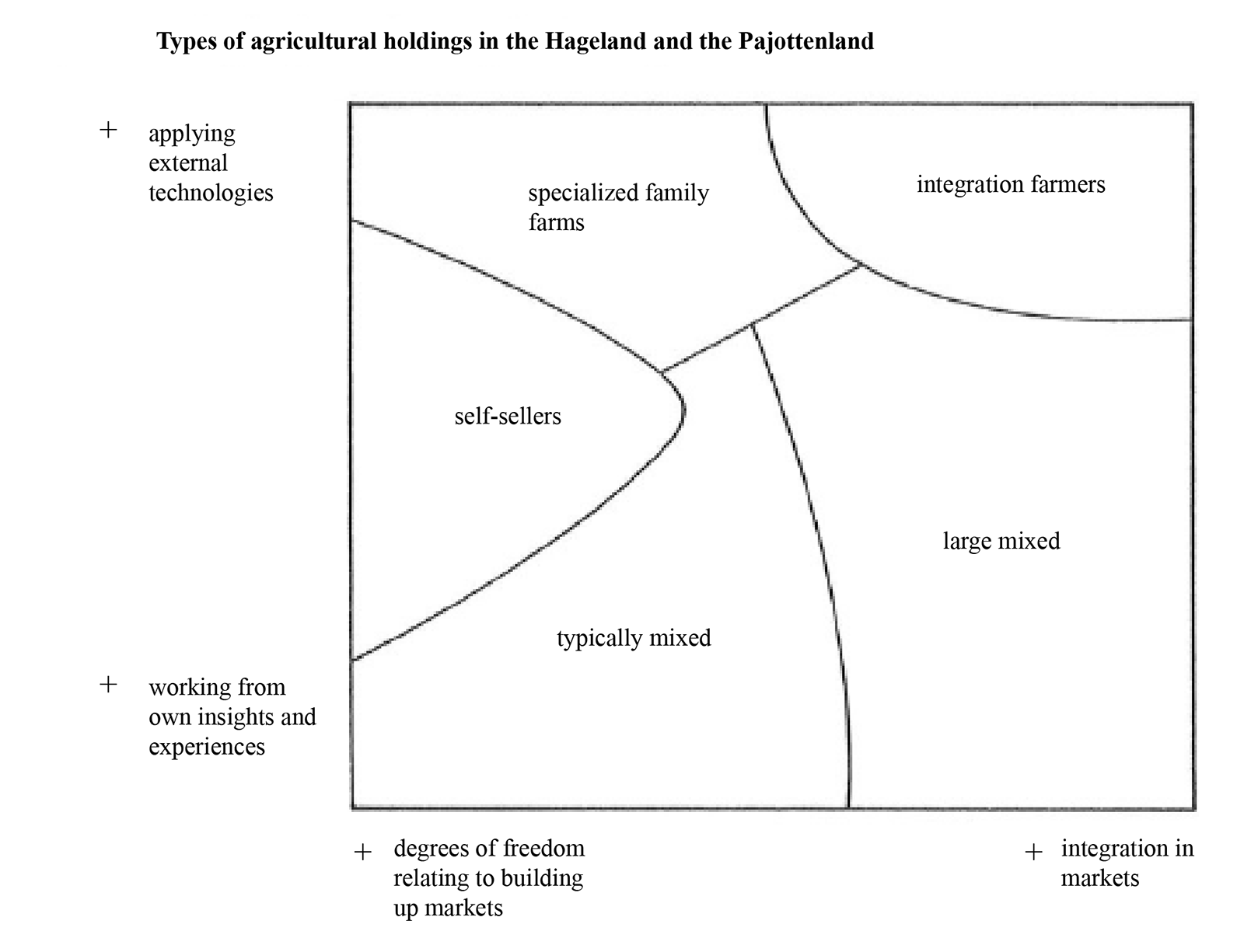

In the diagram at the right page, Greet Kerkhove documents roughly the diversity in the agricultural holdings of the Pajottenland [Kerkhove, 1994, p. 27]. The x-axis shows the degree of market dependence, while the y-axis represents the application of external technology. In this way, she distinguishes five types. In the top corner, we see ‘integration farmers’, large scale monocrop producers, describing themselves more as ‘companies’ than as ‘farms’. They were at the time still a relative minority in the Pajottenland but, as she notes, were by far the fastest growing group. The second group is the ‘specialized family farms’. These are not the only family-driven farms in the region (except the integration farmers, all still are), but they explicitly want to distinguish themselves from the integration farmers, with whom they have the focus on specialisation and technology (more input for more output) in common, but want to remain relatively small scale and independent. The third group, the ‘self-sellers’, are very close to the Boerkozen-type and specialize in a selection of demand-driven crops but want to retain autonomy by selling their produce directly. The fourth group, ‘large mixed’ is less based on technological input, but aims to overcome market fluctuations by using the advantage of scale in combination with a wide variety of products. The last group is the ‘typically mixed’. A smaller area is one distinctive criterion between ‘large mixed’ and ‘typically mixed’, but not the most important. While ‘large mixed’ is located on the ‘integration’ side of the graph, ‘typically mixed’ prefers the ‘autonomy’ side. The farm is built up step by step, based on own resources and labour. New techniques are used insofar as they can be used in the existing situation. Even in terms of degree of specialization, they are rather opposites. In the case of ‘large mixed’, the branches are still relatively separate from each other, while ‘typically mixed’ is looking for strong cross-connections and propagates agroecological principles. Central to ‘typically mixed’ is therefore the continued independence of borrowed capital through a low, gradual spending strategy [Kerkhove, 1994, p. 27].

Business styles in the Hague and the Pajottenland

The Boerkoos on the Verge

One of the major post-war changes was the strong and steady rise in commercial vegetable cultivation. Market-gardening still allowed farmers with predominantly small plots of land to obtain a viable farm. Also many factory workers, on the side, cultivated vegetables in a small piece of land for commercial purposes [CAG]. The Boerkozen tradition around Brussels therefore continued to thrive, still having over a thousand members in the period between 1945 and 1975 [12]. However, they mainly specialized in a niche with a high degree of specialization, focused on the specific Brussels daily early market on the Grand Place. The Boerkozen profited from general post-war reconstruction strategies, but parallel to their large numbers, it was mainly the food industry and suburbanisation that was going through a boom. New production and preservation techniques, the invention and availability of the fridge, a greater overall supply of fruit and vegetables through the reorientation from arable farming to market-gardening, a shift of focus from quality to quantity, the decreasing importance of spatial proximity due to large infrastructure facilities and increasing prosperity will steadily introduce a new agricultural model that will heavily compete with the fresh market’s importance [CAG].

Maraîchers at the morning marker of the Grand Place, Bruxelles (1900)

[12] Monique Wylock, Traditie in de keijken:Boerkozen, Erfgoed Pajottenland Zennevallei, https://www.erfgoedcelpz.be/ traditie-de-kijker-boerkozen

The Birth of Flanders’ Suburbia

As we have seen in the previous part, the urbanization of Belgium was mainly based partly on an anti-urban attitude, most aptly illustrated by the cheap rail infrastructure that spread the workers across the country. The postwar reconstruction programme, however, went even one step further. While in neighbouring countries, postwar architecture and urbanism was being tested by constructing urban ensembles, Belgium focused on the individual home. The most influential of the laws that were passed in those days was undoubtedly the ‘catholic’ (national) De Taeye Act (1948) [AWB, 2012, p. 13]. With substantial government premiums for the acquisition of a first home, combined with cheap credit provision, the legislator tried to encourage as many families as possible to buy or build their own home [Dehaene et.al., 2014]. In addition, compared to earlier initiatives, there were hardly any requirements, which meant that almost everyone could obtain the premium. In only twenty years, between 1950 and 1970, over 340.000 new private houses were built [Van Herck et.al., 2016], more than 10% of the total amount of households at the time [13]. The De Taeye Act also provided a purchase premium for social housing from recognized construction companies. The policy focus thus shifted to the massive acquisition of ownership of new single-family homes [AWB, 2012, p. 13]. Again, this strategy can be perceived to be a political one, as it had as explicit purpose to maintain social order and peace and, by providing private investment to everyone, boost the economy. The downside was that this massive encouragement of individual housing would lead to the total fragmentation of the built-up landscape in Flanders until the abolishment of the law in 1975. But even later, the continuous speculative nature of the urban land market would be reinforced by a flexible economy with high mobility of capital, where areas and cities are competing with each other through infrastructure works, tax cuts and investment subsidies [Kesteloot, 2003]. It would all build up to the territory later coined as the Horizontal Metropolis.

Typical propaganda for the villa, Vlaanderen, Volume 45

[13] P. Deboosere et. al., Huishoudens en gezinnen in Belgie (2009), https://statbel.fgov.be/sites/ default/files/OverStatbelFR/ Sociaal-Economische%20 Enqu%C3%AAte%202001%20-%20 monografie%204-Huishoudens%20 en%20gezinnen%20in%20 Belgi%C3%AB.pdf

Website Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis, available at https://cagnet.be/page/home [consulted November 2019]

Van den Abeele, Lucas (2018): ‘Co-developing a cereal network in Pajottenland, Belgium.’, Master’s Thesis at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås.

Kerkhove, Greet (1994): ‘Sterk gemengd: een socio-economische analyse van agrarische bedrijvigheid in het Hageland en Pajottenland, België.’, Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, Wageningen.

De Troch, Wies (1981): ‘Boerenmarkten: heimwee of weerbaarheid?’, in De Nieuwe Maand – Tijdschrift voor politieke vernieuwing, November 1981, pp. 647-657

Architecture Workroom Brussels (2012): ‘Naar een Visionaire Woningbouw. Kansen en opgaven voor een trendbreuk in de Vlaamse woonproductie’, Team Vlaams Bouwmeester, Brussel.

Dehaene, Michiel, De Vree, Daan & Dumont, Martin (2014): ‘Studie naar modaliteiten van verandering en ruimtelijke transformaties. Ontwerpmatig onderzoek.’, in ‘Ontwerpmatig onderzoek en ruimtelijke transformatie’, Ruimte Vlaanderen, Brussel.

Van Herck K., Vandeweghe E., Verhelst J. (2016): ‘Goed wonen voor iedereen: een rijke geschiedenis. Onderzoek naar de erfgoedwaarden van het sociale woningbouwpatrimonium in Vlaanderen’, in Onderzoeksrapport Onroerend Erfgoed 52, Brussel.

Kesteloot, Chris (2003) ‘Verstedelijking in Vlaanderen: problemen, kansen en uitdagingen voor het beleid in de 21e eeuw’. In Boudry, Linda et.al: ‘De eeuw van de stad. Over stadsrepublieken en rastersteden. Voorstudies.’, Die Keure, Brugge, pp. 15-40.