Insert Infographic: combination of trends

The potential for food growing in London must also be understood within the wider UK agricultural context. The UK’s agricultural workforce is aging and male dominated. It is also the least diverse occupation in the UK with only 1.4% of agricultural workers from ethnic minority backgrounds [Norrie, 2017]. Moreover, Brexit has resulted in uncertainty. This is causing stress and anxiety for farmers and preventing them from adequately planning for the future, including taking the steps urgently needed to tackle the negative environmental impacts of agriculture and prepare for the impacts of climate change. Below we examine the national patterns around farm succession, self-sufficiency, and organic production, to highlight the challenges facing the UK agriculture sector as a whole, before delving into the context of farming in London, the barriers to this, and the solutions food growing in the city could offer.

Age of Farmers

Only 3% of farmers in the UK are under 35, and the percentage of farmers over 65 has been steadily increasing over recent years. Getting into farming is difficult for those without a family background in the sector, due to a lack of affordable land, affordable housing and suitable training. Meanwhile nearly half of current UK farmers do not have a successor, meaning the current trend of farm closure or consolidation is set to continue if action is not taken - one third of UK farms have disappeared in just ten years. Recent research has revealed that although just 3% of young people see farming as an attractive profession, it could meet many of the characteristics they list as important for a fulfilling career, such as working to protect the environment, or staying fit and healthy.

Self-sufficiency

Insert Organic Trend Line

The impacts of Covid-19 and the uncertainties surrounding trade relationships and the future policy landscape for agriculture, because of the UK’s exit from the EU, have drawn attention to the country’s low self-sufficiency in food production, and many farmers’ reliance on subsidies. The gap between UK food imports and exports is widening, and EU countries are both the biggest suppliers of and markets for UK food. The government estimates that fewer than 50% of farms in the UK could cover the costs of their inputs from the market alone, leaving them dependent on subsidies, such as the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy payments. Current subsidy schemes have created perverse incentives when it comes to the environmental management of farmland and tend to favour large landowners over small farmers. There is recognition that the system of subsidy payments will need to be restructured after Brexit, but despite a commitment to ensuring that public money delivers public goods, a lack of clarity on government priorities is making it impossible for farmers to plan at the five to ten year timescale they need to make the major changes required to address the climate emergency.

Organic Farming

Only 2.7% of UK agricultural holdings are farmed organically, (falling since the last peak around 2008/9), the sector is responsible for 10% of UK greenhouse gas emissions (with particularly high methane and nitrous oxide emissions), and there have been warnings that soil fertility could be exhausted within a generation.

Clearly, urgent action is needed to deal with the interconnected social, environmental and economic crises the UK agricultural sector is facing, and to ensure farmers make a decent income whilst producing good quality food and protecting the environment. Currently national policy and funding frameworks are largely devised to help rural farmers rather than recognising the public value created by urban growers, such as increasing food security, managing urban resources, improving the environment, raising awareness of food growing and healthy eating, providing education, health and wellbeing services, and creating pathways into farming as a vocation for a new generation of growers.

Agriculture in Greater London

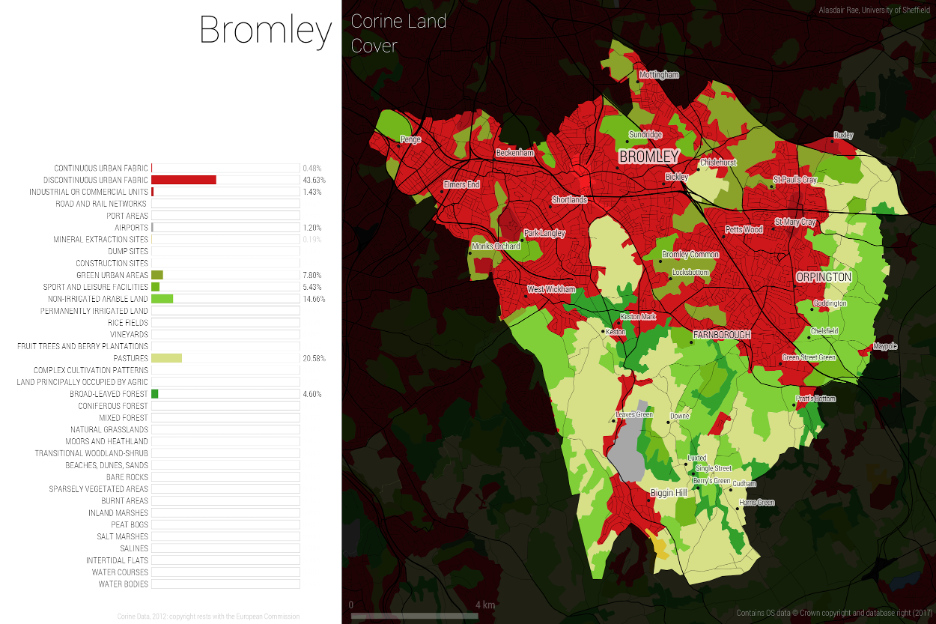

Bromley, the London borough with the highest proportion of agricultural land

Currently, there are over 200 farms in the Greater London area, primarily at the edge of the city in the Green Belt. They cover 11,000 hectares, or about a third of the Green Belt area. The average London farm, at 53 hectares, is smaller than the average English farm (86 hectares). London supports a range of farms, including arable, horticulture, grazing and mixed farms, and 3,000 people are employed in agriculture within London. The 2010 Cultivating the Capital[40] report estimated that London’s farms produce 8,400 tonnes of vegetables as well as an approximate 27 tonnes of honey and meat, milk and eggs. In comparison in noted that Londoners consume 2.4 million tonnes of food, most of which is purchased from supermarkets and often imported from across the world.

The boroughs with the greatest proportion of agricultural land are Bromley (35%), Havering (44%), Hillingdon (23%), Enfield (22%) and Barnet (17%), and in these boroughs both pastoral and arable land are common. However, a 2005 study found that a significant proportion of pastoral land is being used for equine purposes rather than food production; almost a third of farmers in Greater London and the surrounding counties reported diversifying to equine activities.

Of the London boroughs only Hillingdon has its own publicly owned farm estate of ‘county farms’. These county farms were established by local authorities across the UK after World War I to provide opportunities for returning service personnel and new entrants to farming. Where they still exist in public ownership they are mainly let to tenant farmers. However other local authorities in London also have other farmland or growing spaces that lease to community or educational organisations on a commercial basis and to facilitate the delivery of wider social and environmental benefits.

For example, Forty Hall Farm is based on land on a 99 year lease from Enfield Council to Capel Manor College. The farm grows food, trains young people, provides employment, hosts community events and sustainably and organically manages 170 acres of land in the Green Belt.

Some local government policies and strategies in place have the potential to better support growing in the city. London has had a Food Strategy in place since 2006, the implementation of which has been delivered by a raft of projects and programmes including Capital Growth, a food growing network that offers support to community gardens and people who grow their own food in London, including access to discounted training, networking events, support with growing to sell and discounts on equipment. It also established the London Food Board, an independent group of experts who work across London’s food system and advise the Mayor and the Greater London Authority on the delivery of the strategy.The most recent Food Strategy was published in 2018 and states that

“The Mayor will work with local councils, private sector partners and food growing charities to support urban farming. He will help Londoners access community gardens to realise the many benefits of food growing for both communities and individuals."

Implementation of the strategy is supported by the London Food Programme which is part of City Hall's Regeneration and Economic Development Policy Unit, reflecting a recognition of the importance of food to London’s economy and its communities. However, sustained and ongoing lobbying by NGOs and community networks is still required to try to ensure that food growing is recognised and protected in the final version of the New London Plan.

The 2018 London Environment Strategy commits the city to be zero carbon by 2050, and that no biodegradable waste will be sent to landfill by 2026. This is supported by the new Resource and Waste Strategy for England which requires every householder and appropriate businesses to be provided with a weekly separate food waste collection. At a local level Sustain publishes an annual league table of local authority action on a range of food issues. One of these is support for community food growing assessed in terms of whether they have; signed up to Capital Growth, recognised the importance of food growing within local planning policy, and encouraged food growing in schools. In 2018, 13 councils are supporting community food growing by taking action across all of the areas described above, eight are taking action across two areas and 10 are taking action across one area. Of the 32 London boroughs 27 recognised the importance of food growing within local planning policy.

With London’s high land prices and constant demand for new housing stock, accessing and protecting land for growing is particularly challenging, but if prioritised and properly supported in urban development plans, could provide a route into the sector for a younger and more diverse group of people interested in growing but also wanting the services and amenities associated with city life, as well as helping tackle the food insecurity faced by many Londoners.

EUROSTAT (2016) Agriculture, forestry and fishery statistics [online] Available at:https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/7777899/KS-FK-16-001-EN-N.pdf/cae3c56f-53e2-404a-9e9e-fb5f57ab49e3[Accessed 23 August 2019]

FarmingUK (2018) Stress and depression common causes of ill health in farming. FarmingUK [online] 1 November. Available at: https://www.farminguk.com/news/stress-and-depression-common-causes-of-ill-health-in-farming_50623.html [Accessed 23 August 2019]

RSA (2019) Our Future in the Land [online] Available at: https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/future-land[Accessed 23 August 2019]

DEFRA (2018) Agriculture in the United Kingdom 2018 [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/815303/AUK_2018_09jul19.pdf[Accessed 23 August 2019]

Access to Land (2018) Europeʼs new farmers Innovative ways to enter farming and access land [online] Available at: https://www.accesstoland.eu/IMG/pdf/a2l_newentrants_handbook.pdf [Accessed 23 August 2019]

CPRE (n.d.) The future of farming and the countryside [online] Available at: https://www.cpre.org.uk/what-we-do/farming-and-food/farming/the-issues [Accessed 23 August 2019]

Barclays (2018) #FarmtheFuture - Inspiring the next generation [online] Available at: https://www.barclays.co.uk/business-banking/business-insight/farmthefuture/ [Accessed 23 August 2019]

NIESR (2017) Agriculture in the UK [online] Available at: https://www.niesr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publications/NIESR%20GE%20Briefing%20Paper%20No.%204%20-%20Agriculture%20in%20the%20UK_0.pdf [Accessed 23 August 2019]

Monbiot, G. (2018) The one good thing about Brexit? Leaving the EU’s disgraceful farming system. The Guardian [online] 10 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/oct/10/brexit-leaving-eu-farming-agriculture [Accessed 23 August 2019]

DEFRA (2018) Health and Harmony: the future for food, farming and the environment in a Green Brexit [online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/684003/future-farming-environment-consult-document.pdf [Accessed 23 August 2019]

McGrath, M. (2018) Final call to save the world from 'climate catastrophe' [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-45775309 [Accessed 23 August 2019]

van der Zee, B. (2017) UK is 30-40 years away from 'eradication of soil fertility', warns Gove. The Guardian [online] 24 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/oct/24/uk-30-40-years-away-eradication-soil-fertility-warns-michael-gove[Accessed 23 August 2019]

London Assembly (2010) Cultivating the Capital: Food growing and the planning system in London [online] Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/gla_migrate_files_destination/archives/archive-assembly-reports-plansd-growing-food.pdf[Accessed 23 August 2019]

Cole, B. et al. (2015). Corine Land Cover 2012 for the UK, Jersey and Guernsey [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.5285/32533dd6-7c1b-43e1-b892-e80d61a5ea1d [Accessed 23 August 2019]

Forty Hall Farm (n.d.) What we do [online] Available at: http://www.fortyhallfarm.org.uk/what-we-do.html [Accessed 23 August 2019]

London Assembly (n.d.) Food Poverty Action Plans [online]