The city of Rosario (Province of Santa Fe) and its metropolitan region present territorial organization logics and functioning dynamics strongly influenced by a market associated with the production and export of commodities. Its unbeatable geographical conditions as a natural port with access to the Northeast of Argentina and the Atlantic, and its condition as a service center of an extraordinarily agro-productive region, imply a flow of foreign currency which, articulated with the financial market, constitutes an effective device of economic growth, attractive for businesses not always framed within legal structures. The real estate market, historically involved in the development of the city and its context, is functional to these dynamics of economic growth.

In this context, the speculative real estate pressure on the peri-urban and surrounding rural agricultural land constitutes a permanent risk in view of the vital need to recover, protect and enhance the land destined to food production in the vicinity. The progressive disappearance of horticultural establishments that make up Rosario's traditional Green Belt is evidence of this pressure, as well as of the advance of industrialized agriculture and the lack of sufficient and effective state resources to decompress this general dynamic. Wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few and poverty increases within the framework of this logic, intensified in each of Argentina's repeated political-economic crises.

Based on the traditional knowledge of the immigrant population, a valuable urban and peri-urban agro-ecological development has been taking place in the city and in other localities of the Metropolitan Area for the last thirty years, through the effective production of land by means of different operational strategies carried out by a platform of diverse actors and promoted by sustained municipal public policies. This process and the spatial, social, economic, ecological-environmental and political achievements are part of the heritage of the population of Rosario.

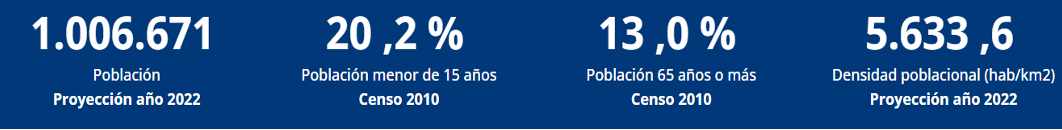

Population dynamics

According to the 2010 National Census (INDEC), 71% of the residents were born in the city of Rosario, 16% come from other provinces of the country and 9% from other localities of the province. According to a study carried out by the Provincial Institute of Statistics of the province of Santa Fe on data from the 2010 National Census, it was revealed that for the first time in the history of the Censuses, immigrants from Paraguay surpassed Italians, who until then had been the largest minority throughout all known census records. Other 59 migrant groups of medium importance came from Peru, Bolivia, Brazil and Uruguay, among others.

In fact, the majority of Rosarinos are descendants of European peoples, mainly Italians - the majority nationality in Rosario - and Spaniards. However, although with lesser presence, also arrived to the city and its region: British, Irish, French, Germans, Swiss, Greeks, Ukrainians, Croatians, Turks, Arabs (mainly Syrians and Lebanese). Other migratory currents quantitatively less representative were made up of Poles and Russians -many of the latter belonging to the Jewish people-.

Since the crisis of 1930, Rosario has received an important flow of internal migration, which has been accentuated since the mid-1940s. During the last decades these migrations come mainly from the interior of Santa Fe, and from the province of Chaco (northeast of the country) and from the aboriginal ethnic group Toba/Gom, who, living in extreme poverty in their place of origin, look for a better destiny in the big city.

European immigrants, mainly Italians, brought with them knowledge and customs associated with food cultivation, which were progressively integrated into the local culture. This knowledge, practices and customs were relevant for the subsistence of the newcomers, whether for rural work or for the domestic production of species for self-consumption. The same happened with the settlers from northern Argentina, who arrived in the cities in search of better living conditions and, later, with immigrants from neighboring countries. This knowledge and practices, together with the availability of fertile soil, gave rise to local processes at different scales, from the formation of peri-urban farms, components of the Rosario green belt, to home gardens. This series of events constitutes the fertile substratum on which the agroecological development of the city is based.

Population Data of the Rosario Metropolitan Area. 1.501880 habitantes (Estimated from Census 2022)

European woman cultivating

Qom inhabitants of the Chaco cultivating

Bolivian farmers cultivating in their country

Local socio-economic Dynamics

Greater Rosario is one of the world's largest soybean and by-product export hubs, with more than 80% of the country's cereal and by-product exports being shipped from its ports. This makes it one of the main grain and financial markets in Argentina and one of the most important agricultural regions in the world. Under this logic, wealth is concentrated in small sectors and there is a growing number of people living in poverty (38.3% INDEC, 2020) and a high percentage of indigent people (7.4% INDEC, 2022).

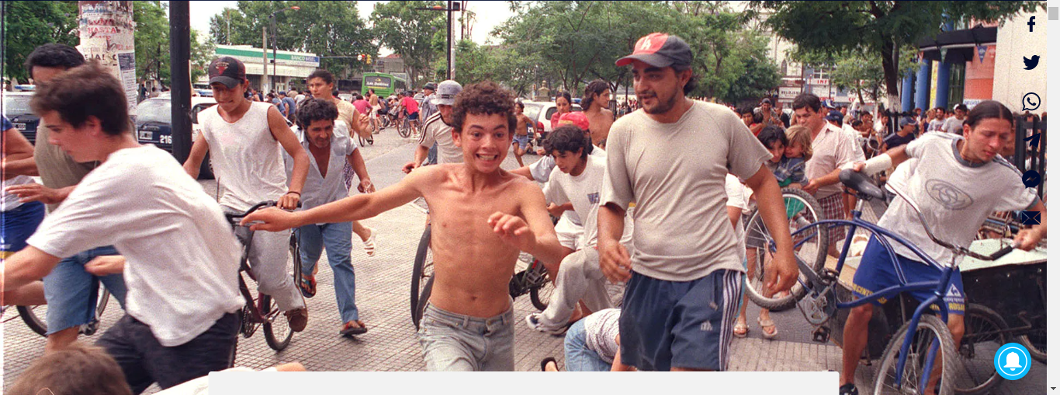

Serious political and economic crises at the national level during the last thirty-five years (1989, 2001, 2008) have had a significant impact, not only on the social but also on the urban structure of Rosario. Poverty and indigence increased after each crisis, configuring a fluctuating dynamic that is maintained. This dynamic was aggravated by the climate emergency and the crisis caused by COVID19. In a context of health vulnerability, progressively unfavorable weather conditions and energy deficit, informal work and "self-employment" are on the rise. Wages are falling while food prices are rising. The increase in taxes, in addition to the high inflationary indexes, destabilizes and/or breaks the middle classes, while many poor sectors increase their indigence.

These recurrent crises, affect the population as a whole but especially the most vulnerable. In Rosario more than one hundred thousand people live in irregular settlements (112 settlements registered during the National Survey of Popular Neighborhoods carried out in 2019). In these settlements, more than 90% of the dwellings do not have basic water, sewage, gas, or storm drains. They only have informal power lines, with the consequent risks. During economic crises, the vulnerable population is the most affected. State assistance to these groups is generally based on the provision of food, medicines and other basic products. During the 2001 crisis, which hit the city of Rosario in particular, the Urban Agriculture Program was implemented, which massively promoted the installation of group orchards and numerous family vegetable gardens were developed to gain access to food. The municipality provided accompaniment, seeds, tools and economic support to those who participated in the projects. The traditional knowledge of people from the north of the country, accustomed to growing food and medicinal plants, was of great value in these initiatives. Some of the people who worked in these gardens sustained the activity by becoming "Urban Gardeners" through production in Group Gardens and Garden Parks, and commercialization in Agroecological Fairs.

Regarding vegetable production in the peri-urban as a source of income, which occupied a relatively significant place in the region decades ago (9,495 hectares according to the INTA 1985 horticultural census in the Gran Rosario region), and whose dynamics consisted of the transfer of land and work generation after generation, it should be noted that it has declined significantly (2,929 hectares according to the INTA 2021 Census). One of the reasons is that their sons and daughters do not work with their parents as they did traditionally. The horticultural activity is currently carried out by 30% of families descendants of producers from Italian immigration at the beginning of the 20th century, local producers and mostly by families of small family producers from the neighbouring country of Bolivia, who arrived mainly in the recent 20 years. The latter have serious difficulties in accessing and securing land tenure. Faced with the urgent need to produce healthy food nearby, these processes that are taking place constitute conflicts to be faced and resolved as soon as possible.

The cultivation of vegetables for self-consumption and as an alternative for the achievement of a genuine income, has been a strategy to alleviate unemployment, poverty and hunger during and after the recent socioeconomic crises in the city of Rosario. Within the framework of municipal public policies, the support to initiatives of Non-Governmental Organizations related to the development of Agroecology during the 1990s, the creation of the Urban Agriculture Program in 2002 and, since that moment in a sustained manner through multiple and diverse integrated actions -among which the creation of the Peri-urban Green Belt Project in 2016, requalified as a Program in 2020 (Ordinance 10141/20) should be mentioned- has had the purpose of sustaining and structurally consolidating of intensive and extensive food activity and Agroecology in Rosario.

Port of Rosario

Looting during the hyperinflationary crisis of 1989

Political-economic-financial crisis of 2001

Rural crisis of 2008

Urban dynamics and land transformation

The urban and urbanistic processes that have taken place in Rosario have been shaping a central area of compact and dense structure that extends over the perimeter rings, and a periphery in which urbanization advances in a diffuse and discontinuous way. These characteristics, which are common denominators in Latin American cities where real estate markets press in a speculative manner and without regulations, imply a duality of urban configurations that trigger conflicts related to unlimited densities and inefficient dispersion.

After the creation of Rosario's Urban Agriculture Program in 2002, in the midst of a socioeconomic crisis and with poverty rates of over 50%, a process of analysis, proposals and actions was initiated to optimize the use of vacant land for local food production. The availability of vacant public land with no budget for its intervention and of land that could not be developed but was suitable for agroecological production, made possible the progressive configuration of urban agroecological production spaces.

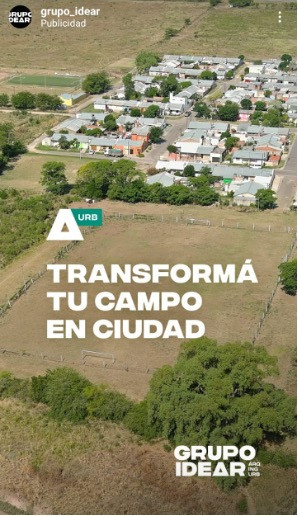

The scarcity and consequent rise in the prices of intra-urban land with infrastructure and services, drives real estate speculation on peri-urban and rural sectors, with low initial cost and high subsequent costs due to the need to build infrastructure and equipment, to which must be added the social and economic costs implicit in the distances to be traveled and the lack of sufficient services and activities. This dynamic includes as a target the land of the traditional "quintas" that made up the Green Belt of Greater Rosario. As a consequence, peri-urban horticultural gardens have been disappearing during the last 50 years, due to the advance of urban and rural borders, causing a greater dependence on the arrival of food from distant places.

The reduction of productive spaces for food production in the city and in the rest of the metropolitan horticultural belt, implied the loss of food autonomy of Rosario and other conurbations, depending largely on the supply of production from other regions of the country. This situation is aggravated by the energy crisis and the climate emergency.

The productive surface that Rosario currently has in the peri-urban area, according to the last survey of November 2021 (carried out by the CVR Project of the Municipality of Rosario), CITA is approximately 1453.3 Ha in the Undeveloped Area (1,146.5 ha with extensive crops and 276 Ha of horticultural crops). 57 productive Units have been identified, of which 10 are dedicated to conventional extensive production, 31 to conventional intensive production, 2 mixed horticultural and conventional extensive units, 9 agroecological intensive units, 1 apicultural unit, 1 floricultural unit, 1 conventional and extensive fruit and vegetable unit, 1 agroecological and conventional intensive unit and 1 agroecological intensive and conventional extensive unit. From 2016 to the present (2022), the peri-urban horticultural area in Rosario has remained at the same level as in 2016.

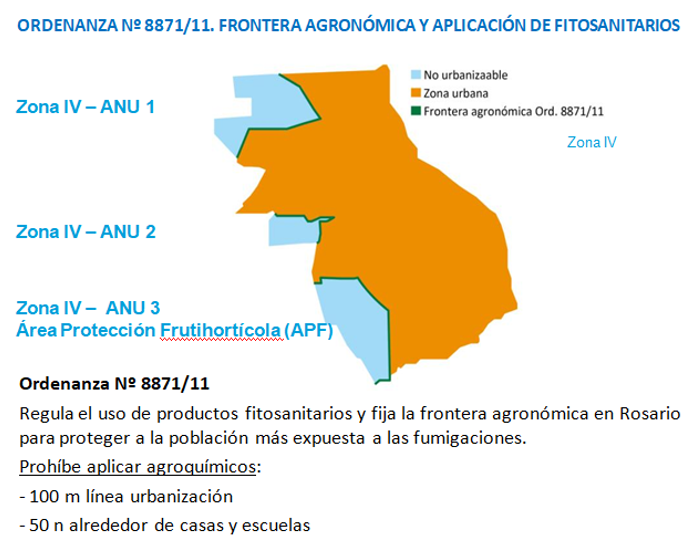

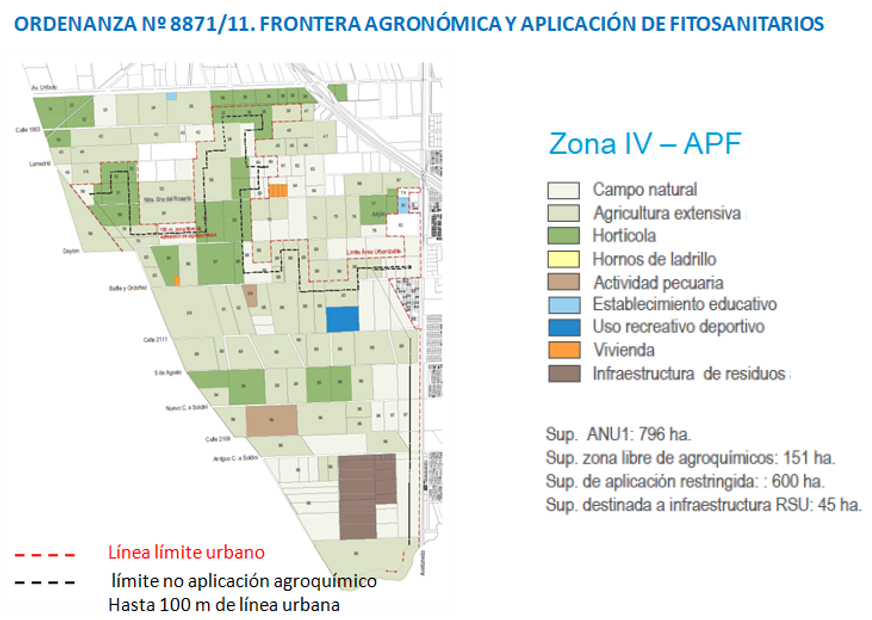

Faced with these realities, in the framework of the Municipality's public policies and in view of the growing number of people affected by the use of agrochemicals, Ordinance No. 8871/11 was passed, which prohibits the application of agrochemicals, setting agronomic boundaries in Rosario that, despite its small area, try to protect the most exposed population from spraying (100 m from urbanization line and 50 m around houses and schools, 50 m from watercourses and agroecological crops).

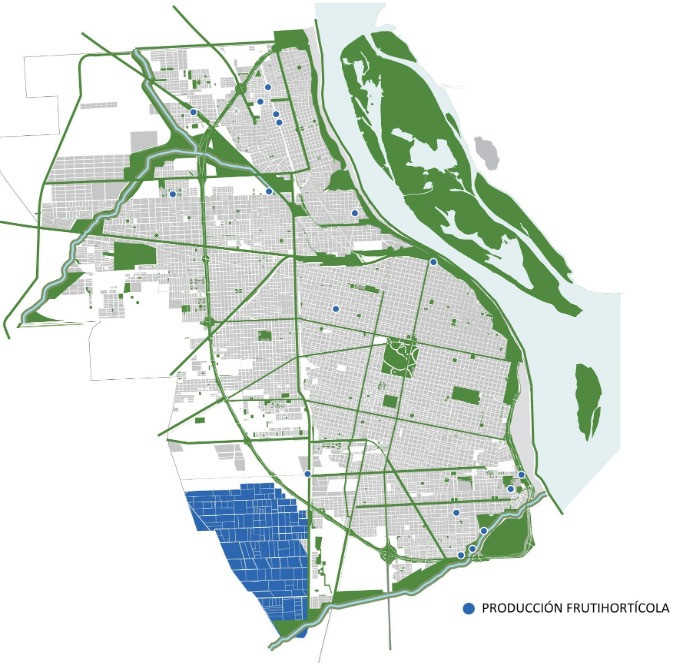

Another relevant measure, during 2013, consisted of protecting, through Municipal Ordinance (Ord 9144/2013), 800 hectares regulated for fruit and vegetable production, promoting agroecological production. Three years later, with the creation of the Rosario Green Belt Project, under the auspices of the Secretaries of Economic Development and Employment, Environment and Public Space and Health of the Municipality of Rosario, active work began to control and promote good agricultural practices and promote the transition to agroecological methods through training and technical advice. It is worth mentioning that Bolivian producers working in establishments in the periurban area of Rosario have adopted these methods, contributing to the process of resistance aimed at protecting the soil and access to healthy food nearby.

It is important to mention that during 2020 a strong real estate pressure was exerted to modify the land use of a large part of the 800 hectares regulated for fruit and vegetable production. This process resulted in a productive land proposal that reclassified the fruit and vegetable land as industrial, presented to the Rosario City Council at the end of the year. The proposal for a change of use was striking, considering that 70% of the industrial land in Rosario was vacant at the time of the presentation, according to the last survey conducted by the Metropolitan Coordination Entity (ECOM) in 2021. “The cause of such vacancy is the lack of infrastructure and services in the areas qualified for industrial uses" (Barenboim, 2022). It should be clarified that fruit and vegetable protection areas similarly lack infrastructure and services necessary for industry.

After strong resistance from NGOs, quinteros/as and part of the Rosario City Council, most of this land was preserved and the Integral Plan for Productive Land and Productive Investments (Ord. 10139/2020) was approved, which incorporates figures of interest, such as the Periurban Agricultural Park (Ord 10142/2020) and creates the Sustainable Food Production Program (Ord 10141/2020).

Rosario: dens & compact areas

Periphery: diffused and discontinued

Real estate advertising

Horticultural garden of 6 Has in the southwest sector of the city resisting the advance of the urban frontier.

Retraction of horticultural land over the last sixty years in the Periurban Area of the Municipality of Rosario.

Supplying of horticultural products from other regions of the country

Phytosanitary barriers in the fruit and vegetable area in the southwest periurban quadrant

Periurban Southwest of Rosario, Fruit and Vegetable Protection Zone

Territorial dynamics associated with the provision of environmental services

Changes in rural land production modalities (industrialized agriculture and transgenic crops), and diffuse urban expansion, have been destroying the territorial green infrastructure of the city and its region, of which the horticultural gardens and farms were an important component. In the context of climate change, these processes produce serious conflicts related especially to high temperatures, alterations in the rainfall regime and the serious productive and sanitary consequences implied.

Likewise, the agro-technological "package" destroys natural soil conditions, affects air, water, flora and fauna, and discontinues ecosystemic functions that make viable the environmental services that are indispensable for sustaining natural, modified and anthropic systems.

Faced with the serious and growing conflicts to be solved within the framework of urban management (floods, high temperatures, energy deficit, difficulties in transporting food produced at a distance, health risks due to fumigations and ingestion of contaminants, increasing volumes of waste that are difficult to transport and store, etc.), local decision-makers and technicians in charge of managing the relevant areas began to value the multiple advantages of agroecological practices and food production in the vicinity as contributions to the solution of these problems.

In fact, the information built from the analysis of the effects of agroecological production in the vicinity to reduce food miles and GHG emissions in Rosario, and of the positive impact of agroecological practices on the performance of spaces with vegetation cover to reduce the risk of flooding and the urban heat island, made it possible to quantify the indispensable environmental services provided by agroecology to the city and its population.

It is worth mentioning that the technical teams of the UA and the PCVR, together with horticultural gardeners and peri-urban producers, have developed a great deal of experience in composting techniques for the improvement of productive soil. These practices demand nutrients that constitute urban organic waste, so their use implies optimizing a problematic flow within the city by channeling virtuous metabolisms through composting. Agroecological soil is a "living" soil in which ecosystemic functions take place that make viable the provision of environmental services of supply, regulation and support. These aspects have been evaluated and quantified, showing significant improvements with respect to soil under conventional cultivation methods.

"To the contributions that Urban and Periurban Agriculture (UPA) contributes to a more sustainable development (in its three dimensions, economic, environmental and social), it is important the role it plays in relation to food security, employment generation, generation of ecosystem services; aspects that show us the multifunctionality of this type of agriculture" (Van Veenhuizen, 2006; Aubry et al, 2012).

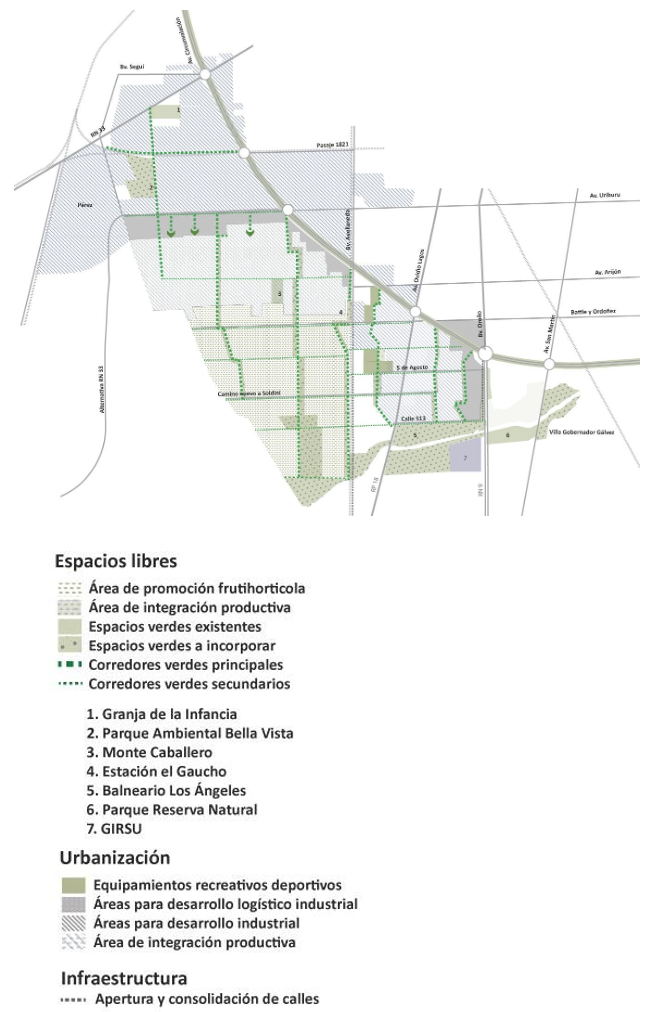

The integrated management of the PAU and the PCVR with other municipal units that operate in territorial planning has been based on the diversity of advantages mentioned that can be obtained from agroecological development. An articulating line of action is defined in terms of the need to progressively create a system of food production and value addition, integrated to the green infrastructure, to the productive occupation ecologically compatible with certain sensitive areas to be protected, and to the protection of irreplaceable environmental services. This vision has determined the incorporation of Agroecology as a productive-spatial strategy in Rosario's urban and peri-urban territorial planning instruments.

Climatic impact. Alteration of rainfall regimes.

Desertification

Drought

Regulated Fruit and Vegetable Area integrated to the municipal Green Infrastructure. Rosario Master Plan.

Agroecological Spaces: important components of the Intra and Periurban Green Infrastructure.

Green Infrastructure Planning in Southwest Periurban Quadrant. Rosario Master Plan.

Food dynamics in Argentina

The Center for Studies on Child Nutrition (CESNI), has prepared a report called "The Argentine table in the last two decades. Changes in the pattern of food and nutrient consumption (1996 - 2013)", based on a study where the National Household Expenditure Surveys (ENGHo) of Argentina, from the years 1996-97, 2004-05 and 2012-13 were analyzed. This study made it possible to establish trends over time. The report shows that "the displacement of the traditional diet, based on fresh or minimally processed foods, prepared at home, has changed to a diet based increasingly on ultra-processed foods" (Rivera Domarco, 2016: 13). This is partly interpreted as a deterioration in the quality of the diet added to a high consumption of free sugars, which exceed the limits established by the WHO, with a notorious increase over time.

Also, according to the report, in Argentina "the apparent consumption of food and beverages has changed in the last two decades, highlighting the decrease in the consumption of fruits and vegetables, wheat flour, legumes, beef and milk; and the increase in the consumption of pies and empanadas, pork, semi-processed meat products, yoghurt, soft drinks, juices and ready-to-eat meals. That change is reflected in the intake of critical nutrients such as saturated fats, trans fats, sodium, sugars, fiber, vitamin A and C" (Zapata, Rovirosa and Carmuega, 2016:15).

This is the first study in Argentina that evidences the increased consumption of energy, fats, sugars and sodium from ultra-processed products. The modifications evidenced show a change in the dietary pattern, which is associated with an increase in the acquisition of foods typical of industrialized countries and a reduction in the consumption of traditional foods and with a low level of industrialization, such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, which also require more time for processing. These changes in the dietary pattern have consequences on the nutritional quality of the Argentine diet.

The foods and beverages that have increased their consumption in Argentina country's diet in the last few years are those that are more advertised. Food and beverage marketing and advertising have been identified as one of the determinants of the consumption of foods and beverages of poor nutritional quality, especially among children. Among the strategies used are messages on food, media communication, pricing strategy, easy accessibility, value enhancement and convenience of food.

The WHO identifies excess malnutrition as the main public health problem of this century, and argues that the genesis of this health problem is located in processes of political, economic, social, cultural order: with profound transformations in food systems that led to increased consumption of foods with high sugar, fat and salt content; with a growing tendency to decrease physical activity: in work, household, recreational, leisure tasks and changes in urban planning, modes of transport, among others (FAO and PAHO, 2017).

It is considered that, in order to address the problems of malnutrition in its various forms, it is necessary to implement transformations in the integrality of food systems, and the role of cities in this regard is key. FAO recognizes cities as strategic places and agents for addressing the complex socioeconomic and ecological issues that limit food security and nutrition. In its Urban Food Agenda, it points out that these issues should figure prominently in the planning of sustainable cities. A sustainable food system is one that ensures food security and nutrition for all, in a way that does not compromise the economic, social and environmental foundations for future generations. Dynamics of control and access to healthy foods

A situation that challenges decision makers is related to the toxicity of the inputs used in food production and their quality. It is worth mentioning that, as a result of the surveys periodically carried out by the (Agencia Santafesina de Seguridad Alimentaria (ASSAL) in the two wholesale markets that the city of Rosario has, the presence of phytosanitary residues has been recurrently detected in the vegetables and fruits analyzed (Diario, El Litoral, Santa Fe, 25/7/2017)

"Food safety is a sensitive issue. That is why it is worrying that ASSAL has detected "irregularities" in 30% of the samples of vegetables and fruits it analyzed in the concentrator market of Santa Fe and in the two most important markets of Rosario...".

Although there is an effort to disseminate Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) by different state institutions, these are not adequately implemented by many producers and, even if they were, they would not be enough to produce healthy food.

In the last horticultural census carried out in 2022 by INTA Oliveros and the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences UNR, it is stated that the adoption of GAP is null despite the efforts to raise awareness and train producers. The insufficiency of control mechanisms implies the non-compliance of minimum precautions to preserve the health of farmers and the population in general.

In parallel, the population does not have fluid and massive access to agroecological food, despite the creation of different marketing channels for agroecological vegetables from the management of the Urban Agriculture Program (2002) and the Green Belt Project (2016). Although Rosario's neighbors can purchase fresh and healthy vegetables in the numerous fairs and permanent sales points, the scale is insufficient to supply and guarantee the right to healthy food in an inclusive manner to the majority of the population.

Dynamics of control and access to healthy foods

A situation that challenges decision makers is related to the toxicity of the inputs used in food production and their quality. It is worth mentioning that, as a result of the surveys periodically carried out by the Agencia Santafesina de Seguridad Alimentaria (ASSAL) in the two wholesale markets that the city of Rosario has, the presence of phytosanitary residues has been recurrently detected in the analyzed vegetables and fruits (Diario El Litoral, Santa Fe, 25/7/2017).

"Food safety is a sensitive issue. That is why it is worrying that ASSAL has detected "irregularities" in 30% of the samples of vegetables and fruits it analyzed in the concentrator market of Santa Fe and in the two most important markets of Rosario...".

Although there is an effort to disseminate Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) by different state institutions, these are not adequately implemented by many producers and, even if they were, they would not be enough to produce healthy food.

In the last horticultural census carried out in 2022 by INTA Oliveros and the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, National University or Rosario, it is stated that the adoption of GAP is null despite the efforts to raise awareness and train producers. The insufficiency of control mechanisms implies the non-compliance of minimum precautions to preserve the health of farmers and the population in general.

In parallel, the population does not have fluid and massive access to agroecological food, despite the creation of different marketing channels for agroecological vegetables from the management of the Urban Agriculture Program (2002) and the Green Belt Project (2016). Although Rosario's neighbors can purchase fresh and healthy vegetables in the numerous fairs and permanent sales points, the scale is insufficient to supply and guarantee the right to healthy food in an inclusive manner to the majority of the population.

Dynamics of production and access to agroecological foods

The challenges posed by the aforementioned problems have influenced the decision to implement and maintain agroecological public policies in the Municipality of Rosario, in order to increase the volume and optimize the quality of locally produced food.

In all urban production areas coordinated by the PUA, production is carried out under agrochemical-free modalities.

The PCVR was created to accompany peri-urban producers (intensive and extensive), to propose and train those who produce conventionally (using agrochemicals and transgenics) to develop an agroecological transition.

In a survey conducted by PCVR during 2019 in the peri-urban area of Rosario, a total of only forty-eight producers (intensive and extensive) were registered. Of this total, 50% were intensive producers (vegetables and flowers), 31% extensive (soybean, wheat and corn) and 19% mixed. The total productive area was 1362 hectares. Of the total number of farms surveyed (intensive and extensive), 58% were producing conventionally, 2% were in the process of input substitution, 34% were complementing input substitution and developing management practices, 2% were producing agroecologically only one sector, and about 4% were producing on the entire farm. In other words, 38% were in transition to agroecological systems.

Regarding intensive production farms, 75% were producing conventionally, 20.5% were in agroecological transition and 4.5% were producing under agroecological modalities. The total intensive production area was 207 hectares.

Of the extensive production farms, 58% produced conventionally, 43.5% were in agroecological transition and 3.5% were under agroecological modalities. The total extensive production area was 1104 hectares.

In reference to productive land tenure modalities, only 48% of the intensive and extensive production area was produced by its owners, while the rest was produced under different forms of tenure.

In order to facilitate access to healthy food, different marketing strategies were created through short chains. The most representative modality is the Agroecological Fairs in urban public spaces, created during the first stage of PUA's management (2003) for the sale of the production of urban vegetable gardens and vegetable parks. In the same productive spaces, the direct sale of vegetables takes place, which are also organized in bags for home delivery and sale. This strategy, initiated as an advance sale to raise funds after a period of heavy rains that caused the loss of a seasonal harvest, was later systematized and widely implemented during the pandemic. It was a great alternative for access to fresh vegetables and income at a time complicated by sanitary restrictions.

With the creation of the PCVR, peri-urban producers joined these short chains, which allowed them to sell their production at better prices without intermediaries. This advantage, added to the significant savings in inputs, encouraged the transition to agroecology among many peri-urban producers.

Action-research as a dynamic for strengthening agroecological development within the framework of public policies in Rosario

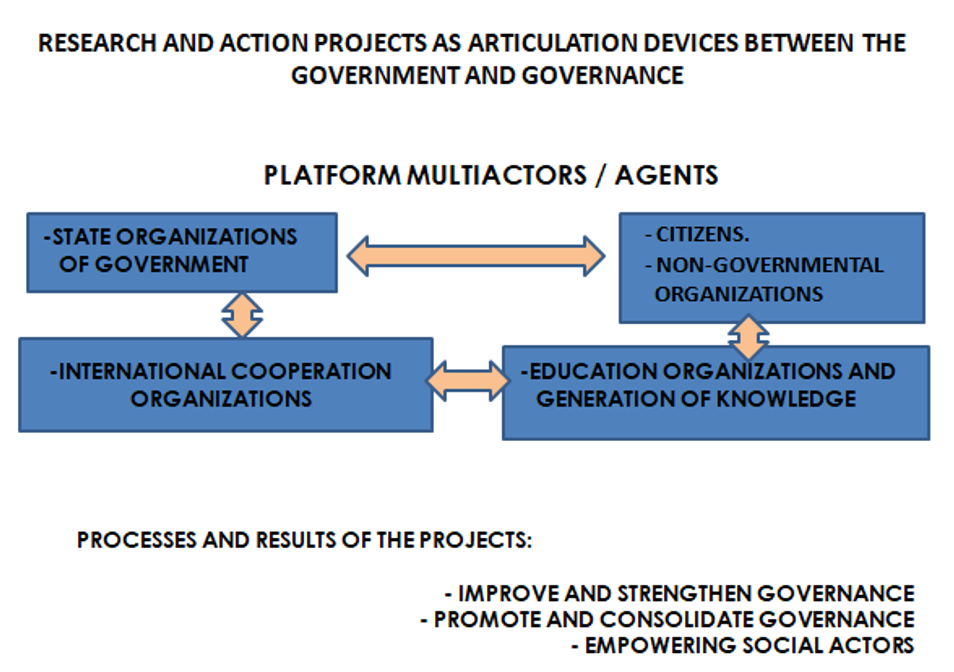

Since 2003 and without interruption until the present (2022), from the PUA first and from 2016 jointly with the PCVR, action-research, inter-institutional, interdisciplinary and participatory projects were developed, subsidized by State and International Funding Agencies. The teams in charge have always been made up of diverse actors, among which agroecological producers play an important role. The topics addressed have responded to the different needs of each stage of the agroecology development process in the city.

The processes and results of these projects have contributed in a concrete and significant way to advance and consolidate the Agroecological development of Rosario.

Among the topics developed, the analysis of urban and peri-urban unbuilt land and the classification and determination of suitability and accessibility for agroecological production were key to plan the land actually available. It was also essential to design the regulatory framework and devices to legalize access and secure land tenure for the new urban farmers, who were beginning to identify themselves and be socially recognized for this role. The participatory design of productive spaces involved the proposal and construction of new spatial typologies and the optimization of ongoing establishments. The construction of indicators to quantify the contributions and advantages of agroecology to mitigate the causes and adapt to the consequences of climate change was of great value to support the need to consolidate existing productive spaces, preserve fruit and vegetable land against the onslaught of real estate speculation, and promote the activity. Projects were also developed, among others, aimed at the participatory design of equipment for productive spaces.

The components of composting and the quality of the products obtained are currently being analyzed, as well as the attributes of agroecological soil in comparison with other soils.

Despite the difficulties and obstacles that need to be resolved, many of the dynamics that have been taking place in the city are promising for the agroecological future of the city of Rosario.

Bibliography

AGUIRRE, P. (2010) Ricos flacos y gordos y pobres: la alimentación en crisis. 1ra ed. Bs As. Capital intelectual S.A.

ARONSKIND, R. (2019.) La hiperinflación de 1989: radiografía del país posdictatorial 1989, el año que nos parió: la hiperinflación. Economía, 16 marzo, 2019 Disponible en la Web: http://espoiler.sociales.uba.ar/2019/03/16/la-hiperinflacion-de-1989-radiografia-del-pais-posdictatorial/

AUBRY, C; Ramamonjisoa, J.; Dabat, M.H, Rakotoarisoa J.;.Rabeharisoa, L.. (2012) URBAN AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE IN CITIES: AN APPROACH WITH THE MULTI-FUNCTIONALITY AND SUSTAINABILITY CONCEPTS IN THE CASE OF ANTANANARIVO (MADAGASCAR). Elsevier, Land Use Policy. Volume 29, Issue 2, April 2012, Pages 429-439

BAREMBOIN, C. (2022). Nota Periodística. Rosario 3. 05-01-2022 - https://www.rosario3.com/-economia-negocios-agro-/Por-falta-de-infraestructura-el-70-del-suelo-industrial-de-Rosario-esta-sin-ocupar-20220115-0006.html

CENSO CINTURÓN HORTÍCOLA DE ROSARIO (2000) (Departamentos Caseros, Constitución, San Jerónimo y Rosario). Regional INTA Santa Fe. Estación Experimental Agropecuaria Oliveros. AER, Arroyo Seco. Estación.

CENSO CINTURÓN HORTÍCOLA DE ROSARIO (2022). Facultad Ciencias Agrarias UNR. Estación Experimental Agropecuaria INTA Oliveros. https://inta.gob.ar/noticias/presentacion-del-censo-del-cinturon-horticola-de-rosario

CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE NUTRICIÓN INFANTIL Informe: “La mesa argentina en las últimas dos décadas. Cambios en el patrón de consumo de alimentos y nutrientes (1996 - 2013)”,

DIARIO LA CAPITAL (2021, diciembre). Nota Periodística. “Las dolorosas imágenes del trágico Diciembre de 2001 “Disponible en la Web: https://www.lacapital.com.ar/fotogalerias/las-dolorosas-imagenes-del-tragico-diciembre-2001-n10003290.html

DIARIO, EL LITORAL, Santa Fe (25/7/2017) Disponible en la Web: https://www.ellitoral.com/area-metropolitana/assal-detecta-irregularidades-30-frutas-verduras_0_jHOs7GzEkg.html)

MUNICIPALIDAD DE ROSARIO - INFORMES ANUALES PROYECTO CINTURÓN VERDE (2018 a 2022). Secretarías de Ambiente y Espacio Público, Desarrollo Económico y Empleo, Salud (instituto de Alimentos).

ENTE DE COORDINACIÓN METROPOLITANO (ECOM), Relevamiento 2021.

ENCUESTAS NACIONALES DE GASTOS DE LOS HOGARES (1996-97, 2004-05 y 2012-13)

INDEC Argentina

Conclusión, 2022. Nota Periodística Paro Ambiental: Organizan una nueva marcha por el clima en Rosario. https://www.conclusion.com.ar/info-general/organizan-nueva-marcha-por-el-clima-en-rosario/10/2022/

Zapata, M.E., Rovirosa, A. Y Carmuega, E. (2016) Cambios en el patrón de consumo de alimentos y bebidas en Argentina, 1996-2013. Vol. 12 Núm. 4 (2016): Alimentación http://revistas.unla.edu.ar/saludcolectiva/article/view/936

Van Veenhuizen, R. (2006). INTRODUCTION: CITIES FARMING FOR THE FUTURE. INTRODUCTION. IN CITIES FARMING FOR THE FUTURE: URBAN AGRICULTURE FOR GREEN AND PRODUCTIVE CITIES (Ed. R. van Veenhuizen), pp. 1–18. Manilla, The Philippines: IIRR/RUAF Foundation/IDRC.